The Levant mine’s man engine, a device of reciprocating ladders and stationary platforms that was installed in the mine (not to be confused with the 10m-high Cornish Mining Man Engine mechanical puppet that did a tour of Cornwall earlier this year), broke while there were over 100 miners using it - a contemporary report in the Cornishman And Cornish Telegraph suggests that there were 130-150 miners on the man engine at the time of the accident. The man engine fell down the shaft, killing 31 of the miners and injuring many others.

The accident was explored in depth in the November 1919 issue of Mining Magazine. The editor Edward Walker wrote: “The accident at Levant was the worst disaster yet experienced at an English non-ferrous metal mine since the flooding of East Wheal Rose in 1846… It is desirable to remind readers that serious accidents also occur with the most up-to-date winding appliances, and that, in any case, the blame for the delay in reorganizing the mining methods at Levant does not rest on the management but with the owners of the mineral rights.”

The Levant mine

According to the National Trust, the UK conservation charity, the Levant mine first appeared on a map in 1748 as an amalgamation of three other early mines - Zawn Brinney, Boscregan and Wheal Unity.

The Levant Mining Company was formed in 1820 with capital of £400. The man engine itself was installed at the mine in 1857, with the aim of transporting miners up and down the workings more quickly and easily.

Also writing in the November 1919 issue of Mining Magazine, the publication’s unnamed ‘Camborne correspondent’ described the man engine. He wrote: “It will be recalled that at this mine, the miners are lowered to or raised from the various levels by means of a man-engine. This particular man-engine appears to have been installed some 70 years ago, and has been in continuous use ever since.

“The man-engine was introduced from Germany in 1842, in which year the first started to work at the Tresavean mine near Redruth [also in Cornwall]. At the time it was hailed, as indeed it was, as a great improvement on the exhausting and slow method of descending and ascending the mines by means of ladders.

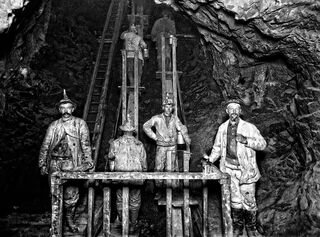

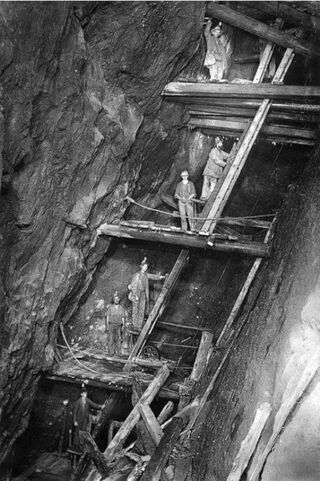

“The man-engine consists of a beam of wood, in 40ft [12.2m] sections bolted together, which extends from the surface to the bottom of the shaft (in this case 1,800ft [548.6m]) which is raised and lowered by a steam engine working at the surface. Attached to the beam or rod, 12ft apart, are steps, each of which affords a foothold for one person, while on the other side of the shaft are stationary platforms also 12ft apart.

“When the beam is at the bottom of its stroke, a man ascending steps on one of the small platforms attached to the rod. The beam rises 12ft and the man then transfers himself to one of the platforms fixed to the side of the shaft. At the bottom of the next stroke, he steps on to the rod again, is raised another 12ft, and then again transfers to a shaft platform. He is thus raised to surface by lifts of 12ft.”

There is an animation of a double-acting man engine here, although the man engine in use at Levant was a single-rod type.

Safety

While the man engine does not sound safe at all by modern mining standards, the miners apparently favoured them over climbing long ladders – part of this is due to the fact that their pay was not calculated until they reached the face, and the man engine got them in and out of the mines more quickly.

Indeed, contemporary safety studies concluded that the use of a man engine was actually safer in practice than using long ladders as there was less danger of them falling off due to exhaustion.

In the Annual Report of the Royal Institution of Cornwall for 1848, published six years after the introduction of the first man engine at the Tresavean and United Mines, looked at the frequency of accidents, the amount of disease and the facility of labour in the deeper levels of those mines since the adoption of the man engine.

George A Michell, one of the surgeons to the Tresavean and United Mines, wrote: “From my observations I should say that pulmonary and cardiac diseases are certainly of less frequent occurrence in this district than before the introduction of the Man Engine, and that the miner, independent of the evil effects of climbing on the respiratory and circulatory organs, has not his strength so exhausted or his constitution so weakened as was formerly the case, and consequently his power of resisting disease is greatly increased.

“I have never conversed with a miner having the benefit of the Man Engine, who did not express himself highly pleased with it, and say that he can perform much more labour than he could before its introduction, and that he returns to his home less fatigued and better able to resume his work on the following day. Climbing from the deep mines was undoubtedly the severest part of his employment, and very probably told more on his constitution than any thing else connected with his occupation. I am confidently of the opinion that the statistics of the next ten years will forcibly show, that the use of the Man Engine in this neighbourhood has tended to increase the average duration of the miner’s life; and that it does now add much to his comfort and health, cannot for a moment be doubted.

“Independent of the benefit of the Man Engine already stated, its superiority over the old method of using ladders, as regards the safety of the miner, is very evident. Since its introduction in Tresavean and the United Mines, there have been only five cases of accident connected with its use; two in Tresavean, and three in the United Mines. In Tresavean the accidents, which were fatal, happened to two boys, both having suffered severe concussion of the brain, with compound fracture of the skull. The three injuries in the United Mines were trifling ones, the severest of them being a contusion of the foot, now under my care, which the patient himself confesses to have been caused through carelessness.

“I have no hesitation in saying, and my opinion is confirmed by parties competent of judging, that there has scarcely happened one eighth part of the accidents from ascent and descent by the Man Engine as was the case by the old system of climbing: many probably might be inclined to doubt the correctness of this assertion, but I do not make it without due consideration, and ample enquiries from parties connected with the mines thus privileged.”

Captain Joseph Jennings, one of the principal agents superintending the workings of Tresavean and United Mines, rationalised it thus: “Look at a man climbing the ladders, he has to lift himself 6 times by one hand and leg in every fathom. If he weighs 1.5 cwt [76kg], or 8 score and 8lbs, in climbing 345 fathoms [631m], which is from the bottom of our mine, he lifts 153 tons 18 cwt one foot high. By the Man Engine he has only to step from side to side once every 12 feet, in the ladder he must step 12 times in 12 feet, so it is clear that there is twelve times the danger in climbing the ladder.”

However, at the time of the accident in 1919, the Levant mine was one of the last mines to use a man engine and there were plans to sink a vertical shaft and install a gig for raising and lowering the miners. Mining Magazine’s Camborne correspondent noted: “The Levant man-engine was the only one left in Cornwall, and its supersession was only a matter of a year or two, for as indicated in these columns last month, a new vertical shaft has been decided on and the winding engine for it has already been purchased.”

The Levant accident

Mining Magazine’s Camborne correspondent also described the Levant mine accident in the November 1919 issue. He wrote: “This famous old mine, the workings of which extend for over one mile under the sea at St Just, was recently the scene of one of the worst disasters ever recorded in the long annals of Cornish mining, no less than 31 lives having been lost.

“On October 20, at a time when the day-shift men were on their way to the surface, the connecting link between the beam of the engine and the wooden rod, which works in the shaft, broke, and the rod collapsed, knocking away the platforms, and generally wrecking the shaft, particularly in that part above the 130 fm. level. At the time, it is stated, about 120 men were on their way to surface, and most were on the rod, as the engine was at the top of its stroke at the time of the accident. Some of the men were precipitated down the shaft; others were crushed or injured by the falling debris.

“To get out the killed and injured was a very hazardous task in view of the wrecked nature of the shaft, but the unassuming heroism of the Cornish miner was quickly in evidence, and there was no lack of volunteers when called for. Gangs of experienced shaft men were appealed for from other mines, and those men from Geevor, East Pool, and other mines, together with uninjured Levant men, worked unceasingly for days, until all the injured and dead were got out.

“We desire to associate ourselves with the many expressions of sympathy extended to the families of the men killed, and also to the management, particularly Major Freathy Oats (chairman of the company), and Captain Ben Nicholas, the manager.”

An article in the Cornishman And Cornish Telegraph on October 29, 1919 also depicted the accident: “When the man engine ascends and is at the top of the stroke as on Monday (the men having completed their day's work about 2:30pm), the machine was practically full of men, each one, as it were standing above the head of the other on the projecting step. An instant later all these miners would have stepped off and paused on the side platforms, or sollors, for the next up lift of the engine. That instant meant life or death to thirty or more men.

“The scene was indescribable. The rod released from its top cracked in several places, and the structure crashed down in a mass of debris. As its foot was at the bottom of the shaft it could only have dropped the twelve feet if it had not snapped in other places. The worst chokage was in the upper part of the shaft.”

Robert Penaluna, a young St Just miner who was on the man engine at the time of the accident, explained his experience in the same issue of the Cornishman And Cornish Telegraph. He said: “I was coming up on the man engine three steps below the 150 fathom level. The engine was full of men. We had travelled up part of the way between one sollor [side platform] and another when the engine dropped a little put then picked herself up again. Then she fell away to the bottom. I was thrown on my chest upon the sollor. My chum on the next sollor below (Charlie Freestone, aged 25 of St Just) had his feet caught between the step on which he stood and the sollor, and was swung upside down.

“I was not hurt except that a piece of timber struck me on the leg. For about three hours I was down there before I could come up. Then I walked up the ladder through the pumping engine shaft, to the surface. Before that I picked up Freestone, who was suffering from shock, and dragged him through a manhole on to the sollor upon which I was standing. He fainted in my arms. We got him back to the 150 level shaft and men of the afternoon shift helped to drag Freestone to the surface with ropes. When the engine broke it was a tremendous crash for in dropping she knocked away timber and everything else in her path. The engine rod on which we were traveling shook violently. The smash gave a terrible shook to us all, and everybody lost heart and nerve entirely. The screams of some of the men were awful, as they gripped the rod like grim death. A number of them had the presence to the nearest place, and saved themselves by the skin of their teeth.

“I wouldn't go through an experience like that again for the world.”

Aftermath

The Levant mine’s man engine was not repaired, and the deeper levels of the mine were never worked again. The mine itself closed in 1930, as tin prices had dropped dramatically - between January 1929 to December 1930, the price of tin had dropped from £223 to £112 per tonne.

In 1967, the Levant mine was passed into the care of the National Trust; it is now part of the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site, which has UNESCO World Heritage status. It has also featured as a location in the BBC television adaptation of Poldark, with the Levant mine standing in as the fictional Tressiders rolling mill.